Esophagus Cancer

What is the esophagus?

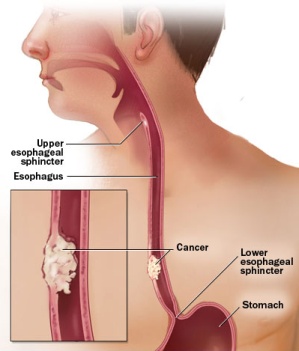

The esophagus is in the chest. It's about 10 inches long.

This organ is part of the digestive tract. Food moves from the mouth through the esophagus to the stomach.

The esophagus is a muscular tube. The wall of the esophagus has several layers:

• Inner layer or lining (mucosa): The lining of the esophagus is moist so that food can pass to the stomach.

• Submucosa: The glands in this layer make mucus. Mucus keeps the esophagus moist.

• Muscle layer: The muscles push the food down to the stomach.

• Outer layer: The outer layer covers the esophagus.

Esophagus cancer facts

• While the exact cause(s) of cancer of the esophagus is not known, risk factors have been identified.

• The risk of cancer of the esophagus is increased by long-term irritation of the esophagus, such as with smoking, heavy alcohol intake, and Barrett's esophagitis.

• Diagnosis of cancer of the esophagus can be made by barium X-ray of the esophagus and confirmed by endoscopy with biopsy of the cancer tissue.

• Cancer of the esophagus can cause difficulty and pain with swallowing solid food.

• Treatment of cancer of the esophagus depends on the size, location, and the extent of cancer spread, as well as the age and health of the patient.

Cancer Cells

Cancer begins in cells, the building blocks that make up tissues. Tissues make up the organs of the body.

Normal cells grow and divide to form new cells as the body needs them. When normal cells grow old or get damaged, they die, and new cells take their place.

Sometimes, this process goes wrong. New cells form when the body does not need them, and old or damaged cells do not die as they should. The buildup of extra cells often forms a mass of tissue called a growth or tumor.

Growths in the wall of the esophagus can be benign (not cancer) or malignant (cancer). The smooth inner wall may have an abnormal rough area, an area of tiny bumps, or a tumor.

Benign growths are not as harmful as malignant growths:

• Benign growths:

o are rarely a threat to life

o can be removed and probably won't grow back

o don't invade the tissues around them

o don't spread to other parts of the body

• Malignant growths:

o may be a threat to life sometimes

o can be removed but can grow back

o can invade and damage nearby tissues and organs

o can spread to other parts of the body

Esophageal cancer begins in cells in the inner layer of the esophagus.

Over time, the cancer may invade more deeply into the esophagus and nearby tissues.

Cancer cells can spread by breaking away from the original tumor. They may enter blood vessels or lymph vessels, which branch into all the tissues of the body. The cancer cells may attach to other tissues and grow to form new tumors that may damage those tissues. The spread of cancer cells is called metastasis. See the Staging section for information about esophageal cancer that has spread.

Types of Esophageal Cancer

There are two main types of esophageal cancer. Both types are diagnosed, treated, and managed in similar ways.

The two most common types are named for how the cancer cells look under a microscope.

Both types begin in cells in the inner lining of the esophagus:

• Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus: This type is usually found in the lower part of the esophagus, near the stomach. In the United States, adenocarcinoma is the most common type of esophageal cancer. It's been increasing since the 1970s.

• Squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus: This type is usually found in the upper part of the esophagus. This type is becoming less common among Americans. Around the world, however, squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type.

Risk Factors

When you get a diagnosis of cancer, it's natural to wonder what may have caused the disease. Doctors can seldom explain why one person develops esophageal cancer and another doesn't. However, we do know that people with certain risk factors are more likely than others to develop esophageal cancer. A risk factor is something that may increase the chance of getting a disease.

Studies have found the following risk factors for esophageal cancer:

• Age 65 or older: Age is the main risk factor for esophageal cancer. The chance of getting this disease goes up as you get older. In the United States, most people are 65 years of age or older when they are diagnosed with esophageal cancer.

• Being male: In the United States, men are more than three times as likely as women to develop esophageal cancer.

• Smoking: People who smoke are more likely than people who don't smoke to develop esophageal cancer.

• Heavy drinking: People who have more than 3 alcoholic drinks each day are more likely than people who don't drink to develop squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus. Heavy drinkers who smoke are at a much higher risk than heavy drinkers who don't smoke. In other words, these two factors act together to increase the risk even more.

• Diet: Studies suggest that having a diet that's low in fruits and vegetables may increase the risk of esophageal cancer. However, results from diet studies don't always agree, and more research is needed to better understand how diet affects the risk of developing esophageal cancer.

• Obesity: Being obese increases the risk of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus.

• Acid reflux: Acid reflux is the abnormal backward flow of stomach acid into the esophagus. Reflux is very common. A symptom of reflux is heartburn, but some people don't have symptoms. The stomach acid can damage the tissue of the esophagus. After many years of reflux, this tissue damage may lead to adenocarcinoma of the esophagus in some people.

• Barrett esophagus: Acid reflux may damage the esophagus and over time cause a condition known as Barrett esophagus. The cells in the lower part of the esophagus are abnormal. Most people who have Barrett esophagus don't know it. The presence of Barrett esophagus increases the risk of adenocarcinoma of the esophagus. It's a greater risk factor than acid reflux alone.

Many other possible risk factors (such as smokeless tobacco) have been studied. Researchers continue to study these possible risk factors.

Having a risk factor doesn't mean that a person will develop cancer of the esophagus. Most people who have risk factors never develop esophageal cancer.

Symptoms

Early esophageal cancer may not cause symptoms. As the cancer grows, the most common symptoms are:

• Food gets stuck in the esophagus, and food may come back up

• Pain when swallowing

• Pain in the chest or back

• Weight loss

• Heartburn

• A hoarse voice or cough that doesn't go away within 2 weeks

These symptoms may be caused by esophageal cancer or other health problems. If you have any of these symptoms, you should tell your doctor so that problems can be diagnosed and treated as early as possible.

Diagnosis

If you have a symptom that suggests esophageal cancer, your doctor must find out whether it's really due to cancer or to some other cause. The doctor gives you a physical exam and asks about your personal and family health history.

You may have blood tests. You also may have:

• Barium swallow: After you drink a barium solution, you have x-rays taken of your esophagus and stomach. The barium solution makes your esophagus show up more clearly on the x-rays. This test is also called an upper GI series.

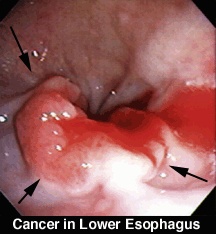

• Endoscopy: The doctor uses a thin, lighted tube (endoscope) to look down your esophagus. The doctor first numbs your throat with an anesthetic spray, and you may also receive medicine to help you relax. The tube is passed through your mouth or nose to the esophagus. The doctor may also call this procedure upper endoscopy, EGD, or esophagoscopy.

• Biopsy: Usually, cancer begins in the inner layer of the esophagus. The doctor uses an endoscope to remove tissue from the esophagus. A pathologist checks the tissue under a microscope for cancer cells. A biopsy is the only sure way to know if cancer cells are present.

You may want to ask the doctor these questions before having a biopsy:

• Where will the procedure take place? Will I have to go to the hospital?

• How long will it take? Will I be awake?

• Will it hurt? Will I get an anesthetic?

• What are the risks? What are the chances of infection or bleeding afterward?

• How do I prepare for the procedure?

• How long will it take me to recover?

• How soon will I know the results? Will I get a copy of the pathology report?

• If I do have cancer, who will talk to me about the next steps? When?

Staging

If the biopsy shows that you have cancer, your doctor needs to learn the extent (stage) of the disease to help you choose the best treatment.

Staging is a careful attempt to find out the following

• how deeply the cancer invades the walls of the esophagus

• whether the cancer invades nearby tissues

• whether the cancer has spread, and if so, to what parts of the body

When esophageal cancer spreads, it's often found in nearby lymph nodes. If cancer has reached these nodes, it may also have spread to other lymph nodes, the bones, or other organs. Also, esophageal cancer may spread to the liver and lungs.

Your doctor may order one or more of the following staging tests:

• Endoscopic ultrasound: The doctor passes a thin, lighted tube (endoscope) down your throat, which has been numbed with anesthetic. A probe at the end of the tube sends out sound waves that you can't hear. The waves bounce off tissues in your esophagus and nearby organs. A computer creates a picture from the echoes. The picture can show how deeply the cancer has invaded the wall of the esophagus. The doctor may use a needle to take tissue samples of lymph nodes.

• CT scan: An x-ray machine linked to a computer takes a series of detailed pictures of your chest and abdomen. Doctors use CT scans to look for esophageal cancer that has spread to lymph nodes and other areas. You may receive contrast material by mouth or by injection into a blood vessel. The contrast material makes abnormal areas easier to see.

• MRI: A strong magnet linked to a computer is used to make detailed pictures of areas inside your body. An MRI can show whether cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other areas. Sometimes contrast material is given by injection into your blood vessel. The contrast material makes abnormal areas show up more clearly on the picture.

• PET scan: You receive an injection of a small amount of radioactive sugar. The radioactive sugar gives off signals that the PET scanner picks up. The PET scanner makes a picture of the places in your body where the sugar is being taken up. Cancer cells show up brighter in the picture because they take up sugar faster than normal cells do. A PET scan shows whether esophageal cancer may have spread.

• Bone scan: You get an injection of a small amount of a radioactive substance. It travels through the bloodstream and collects in the bones. A machine called a scanner detects and measures the radiation. The scanner makes pictures of the bones. The pictures may show cancer that has spread to the bones.

• Laparoscopy: After you are given general anesthesia, the surgeon makes small incisions (cuts) in your abdomen. The surgeon inserts a thin, lighted tube (laparoscope) into the abdomen. Lymph nodes or other tissue samples may be removed to check for cancer cells.

Sometimes staging is not complete until after surgery to remove the cancer and nearby lymph nodes.

When cancer spreads from its original place to another part of the body, the new tumor has the same kind of abnormal cells and the same name as the primary tumor. For example, if esophageal cancer spreads to the liver, the cancer cells in the liver are actually esophageal cancer cells. The disease is metastatic esophageal cancer, not liver cancer. For that reason, it's treated as esophageal cancer, not liver cancer. Doctors call the new tumor "distant" or metastatic disease.

These are the stages of esophageal cancer:

• Stage 0: Abnormal cells are found only in the inner layer of the esophagus. It's called carcinoma in situ.

• Stage I: The cancer has grown through the inner layer to the submucosa. (The picture shows the submucosa and other layers.)

• Stage II is one of the following:

o The cancer has grown through the inner layer to the submucosa, and cancer cells have spread to lymph nodes.

o Or, the cancer has invaded the muscle layer. Cancer cells may be found in lymph nodes.

o Or, the cancer has grown through the outer layer of the esophagus.

• Stage III is one of the following:

o The cancer has grown through the outer layer, and cancer cells have spread to lymph nodes.

o Or, the cancer has invaded nearby structures, such as the airways. Cancer cells may have spread to lymph nodes.

• Stage IV: Cancer cells have spread to distant organs, such as the liver

Treatment

People with esophageal cancer have several treatment options. The options are surgery, radiation therapy, chemotherapy, or a combination of these treatments. For example, radiation therapy and chemotherapy may be given before or after surgery.

The treatment that's right for you depends mainly on the following:

• where the cancer is located within the esophagus

• whether the cancer has invaded nearby structures

• whether the cancer has spread to lymph nodes or other organs

• your symptoms

• your general health

Esophageal cancer is hard to control with current treatments.

For that reason, many doctors encourage people with this disease to consider taking part in a clinical trial, a research study of new treatment methods. Clinical trials are an important option for people with all stages of esophageal cancer. See the Taking Part in Cancer Research section.

You may have a team of specialists to help plan your treatment. Your doctor may refer you to specialists, or you may ask for a referral. You may want to see a gastroenterologist, a doctor who specializes in treating problems of the digestive organs. Other specialists who treat esophageal cancer include thoracic (chest) surgeons, thoracic surgical oncologists, medical oncologists, and radiation oncologists.

Your health care team may also include an oncology nurse and a registered dietitian. If your airways are affected by the cancer, you may have a respiratory therapist as part of your team. If you have trouble swallowing, you may see a speech pathologist.

Your health care team can describe your treatment choices, the expected results of each, and the possible side effects. Because cancer therapy often damages healthy cells and tissues, side effects are common. Before treatment starts, ask your health care team about possible side effects and how treatment may change your normal activities. You and your health care team can work together to develop a treatment plan that meets your needs.

You may want to ask your doctor these questions before your treatment begins:

• What is the stage of the disease? Has the cancer spread? Do any lymph nodes show signs of cancer?

• What is the goal of treatment? What are my treatment choices? Which do you recommend for me? Why?

• Will I have more than one kind of treatment?

• What can I do to prepare for treatment?

• Will I need to stay in the hospital? If so, for how long?

• What are the risks and possible side effects of each treatment? For example, am I likely to have eating problems during or after treatment? How can side effects be managed?

• What will the treatment cost? Will my insurance cover it?

• Would a research study (clinical trial) be appropriate for me?

• Can you recommend other doctors who could give me a second opinion about my treatment options?

• How often should I have checkups?

Surgery

KThere are several types of surgery for esophageal cancer. The type depends mainly on where the cancer is located. The surgeon may remove the whole esophagus or only the part that has the cancer. Usually, the surgeon removes the section of the esophagus with the cancer, lymph nodes, and nearby soft tissues. Part or all of the stomach may also be removed.

You and your surgeon can talk about the types of surgery and which may be right for you.

The surgeon makes incisions into your chest and abdomen to remove the cancer. In most cases, the surgeon pulls up the stomach and joins it to the remaining part of the esophagus. Or a piece of intestine may be used to connect the stomach to the remaining part of the esophagus. T

he surgeon may use either a piece of small intestine or large intestine. If the stomach was removed, a piece of intestine is used to join the remaining part of the esophagus to the small intestine.

During surgery, the surgeon may place a feeding tube into your small intestine. This tube helps you get enough nutrition while you heal. Information about eating after surgery is in the Nutrition section.

You may have pain for the first few days after surgery. However, medicine will help control the pain. Before surgery, you should discuss the plan for pain relief with your health care team.

After surgery, your team can adjust the plan if you need more relief.

Your health care team will watch for signs of food leaking from the newly joined parts of your digestive tract. They will also watch for pneumonia or other infections, breathing problems, bleeding, or other problems that may require treatment.

The time it takes to heal after surgery is different for everyone and depends on the type of surgery. You may be in the hospital for at least one week.

Radiation Therapy

Radiation therapy (also called radiotherapy) uses high-energy rays to kill cancer cells. It affects cells only in the treated area.

Radiation therapy may be used before or after surgery. Or it may be used instead of surgery. Radiation therapy is usually given with chemotherapy to treat esophageal cancer.

Doctors use two types of radiation therapy to treat esophageal cancer.

Some people receive both types:

• External radiation therapy: The radiation comes from a large machine outside the body. The machine aims radiation at your cancer. You may go to a hospital or clinic for treatment. Treatments are usually 5 days a week for several weeks.

• Internal radiation therapy (brachytherapy): The doctor numbs your throat with an anesthetic spray and gives you medicine to help you relax. The doctor puts a tube into your esophagus. The radiation comes from the tube. Once the tube is removed, no radioactivity is left in your body. Usually, only a single treatment is done.

Side effects depend mainly on the dose and type of radiation. External radiation therapy to the chest and abdomen may cause a sore throat, pain similar to heartburn, or pain in the stomach or the intestine. You may have nausea and diarrhea. Your health care team can give you medicines to prevent or control these problems.

Also, your skin in the treated area may become red, dry, and tender.

You may lose hair in the treated area. A much less common side effect of radiation therapy aimed at the chest is harm to the lung, heart, or spinal cord.

You are likely to be very tired during radiation therapy, especially in the later weeks of external radiation therapy.

You may also continue to feel very tired for a few weeks after radiation therapy is completed. Resting is important, but doctors usually advise patients to try to stay as active as they can.

Radiation therapy can lead to problems with swallowing. For example, sometimes radiation therapy can harm the esophagus and make it painful for you to swallow.

Or, the radiation may cause the esophagus to narrow. Before radiation therapy, a plastic tube may be inserted into the esophagus to keep it open. If radiation therapy leads to a problem with swallowing, it may be hard to eat well.

Ask your health care team for help getting good nutrition. See the Nutrition section for more information.

Chemotherapy

Most people with esophageal cancer get chemotherapy. Chemotherapy uses drugs to destroy cancer cells. The drugs for esophageal cancer are usually given through a vein (intravenous). You may have your treatment in a clinic, at the doctor's office, or at home.

Some people need to stay in the hospital for treatment.

Chemotherapy is usually given in cycles. Each cycle has a treatment period followed by a rest period.

The side effects depend mainly on which drugs are given and how much.

Chemotherapy kills fast-growing cancer cells, but the drug can also harm normal cells that divide rapidly:

• Blood cells: When chemotherapy lowers the levels of healthy blood cells, you're more likely to get infections, bruise or bleed easily, and feel very weak and tired. Your health care team will check for low levels of blood cells. If your levels are low, your health care team may stop the chemotherapy for a while or reduce the dose of drug. There also are medicines that can help your body make new blood cells.

• Cells in hair roots: Chemotherapy may cause hair loss. If you lose your hair, it will grow back, but it may change in color and texture.

• Cells that line the digestive tract: Chemotherapy can cause poor appetite, nausea and vomiting, diarrhea, or mouth and lip sores. Your health care team can give you medicines and suggest other ways to help with these problems.

Other possible side effects include a skin rash, joint pain, tingling or numbness in your hands and feet, hearing problems, or swollen feet or legs. Your healthcare team can suggest ways to control many of these problems. Most go away when treatment ends.

Supportive Care

KEsophageal cancer and its treatment can lead to other health problems. You can have supportive care before, during, or after cancer treatment.

Supportive care is treatment to control pain and other symptoms, to relieve the side effects of therapy, and to help you cope with the feelings that a diagnosis of cancer can bring. You may receive supportive care to prevent or control these problems and to improve your comfort and quality of life during treatment.

Cancer Blocks the Esophagus

You may have trouble swallowing because the cancer blocks the esophagus. Not being able to swallow makes it hard or impossible to eat. It also increases the risk of food getting in your airways. This can lead to a lung infection like pneumonia. Also, not being able to swallow liquids or saliva can be very distressing.

Your health care team may suggest one or more of the following options:

• Stent: You get an injection of a medicine to help you relax. The doctor places a stent (a tube made of metal mesh or plastic) in your esophagus. Food and liquid can pass through the center of the tube. However, solid foods need to be chewed well before swallowing. A large swallow of food could get stuck in the stent.

• Laser therapy: A laser is a concentrated beam of intense light that kills tissue with heat.

The doctor uses the laser to destroy the cancer cells blocking the esophagus. Laser therapy may make swallowing easier for a while, but you may need to repeat the treatment several weeks later.

• Photodynamic therapy: You get an injection, and the drug collects in the esophageal cancer cells. Two days after the injection, the doctor uses an endoscope to shine a special light (such as a laser) on the cancer. The drug becomes active when exposed to light. Two or three days later, the doctor may check to see if the cancer cells have been killed. People getting this drug must avoid sunlight for one month or longer. Also, you may need to repeat the treatment several weeks later.

• Radiation therapy: Radiation therapy helps shrink the tumor. If the tumor blocks the esophagus, internal radiation therapy or sometimes external radiation therapy can be used to help make swallowing easier.

• Balloon dilation: The doctor inserts a tube through the blocked part of the esophagus. A balloon helps widen the opening. This method helps improve swallowing for a few days.

• Other ways to get nutrition: See the Nutrition section for ways to get food when eating becomes difficult.

Nutrition

It's important to meet your nutrition needs before, during, and after cancer treatment. You need the right amount of calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals. Getting the right nutrition can help you feel better and have more energy.

However, when you have esophageal cancer, it may be hard to eat for many reasons. You may be uncomfortable or tired, and you may not feel like eating. Also, the cancer may make it hard to swallow food. If you're getting chemotherapy, you may find that foods don't taste as good as they used to. You also may have side effects of treatment such as poor appetite, nausea, vomiting, or diarrhea.

If you develop problems with eating, there are a number of ways to meet your nutrition needs.

A registered dietitian can help you figure out a way to get enough calories, protein, vitamins, and minerals:

• A dietitian may suggest a change in the types of foods you eat. Sometimes changing the texture, fiber, and fat content of your foods can lessen your discomfort.

• A dietitian may also suggest a change in the portion size and meal times.

• A dietitian may recommend liquid meals, such as canned nutrition beverages, milk shakes, or smoothies.

• If swallowing becomes too difficult, your dietitian and your doctor may recommend that you receive nutrition through a feeding tube.

• Sometimes, nutrition is provided directly into the bloodstream with intravenous nutrition.

Nutrition After Surgery

A registered dietitian can help you plan a diet that will meet your nutrition needs. A plan that describes the type and amount of food to eat after surgery can help you prevent weight loss and discomfort with eating.

If your stomach is removed during surgery, you may develop a problem afterward known as the dumping syndrome. This problem occurs when food or liquid enters the small intestine too fast. It can cause cramps, nausea, bloating, diarrhea, and dizziness.

There are steps you can take to help control dumping syndrome:

• Eat smaller meals.

• Drink liquids before or after eating solid meals.

• Limit very sweet foods and drinks, such as cookies, candy, soda, and juices.

Also, your health care team may suggest medicine to control the symptoms.

After surgery, you may need to take daily supplements of vitamins and minerals, such as calcium, and you may need injections of vitamin B12.